Pac-Ztec did not start as an attempt to faithfully recreate Pac-Man.

It began as a technical playground. A way to explore Unity, test ideas, and see how far a familiar concept could be pushed when translated into a full 3D space. There was no roadmap, no production plan, and no promise that it would turn into anything more than a prototype.

But very early on, the project ran into its first real constraint: MOVEMENT

The Weight of a Simple Mechanic

Pac-Man’s movement looks deceptively simple. The character glides through corridors, snaps cleanly into turns, and never drifts off-path. There is no acceleration curve or analog nuance. You press a direction and the game responds with absolute certainty. That precision is the game.

In contrast, most modern 3D games default to free movement systems: analog input, smooth acceleration, physics-based collisions, and continuous turning. Those systems are flexible, expressive, and generally forgiving. They are also noisy. For something like Pac-Ztec, that noise immediately breaks the illusion.

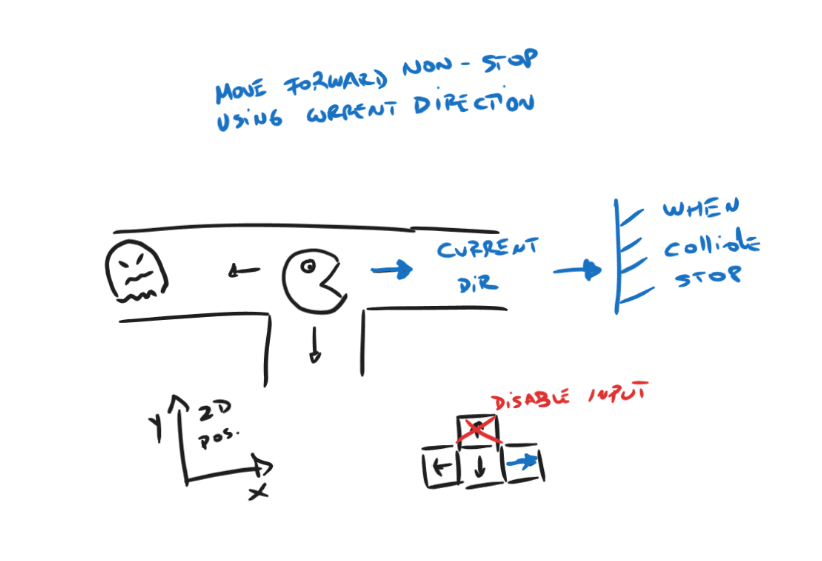

Early sketches trying to reason about 2D movement. Already overthinking inputs… old habits die hard.

Early sketches trying to reason about 2D movement. Already overthinking inputs… old habits die hard.

Movement in Pac-Man is not just another system layered on top of the game. It is the game. Every decision, every mistake, every narrow escape is rooted in how movement behaves. Classic Pac-Man movement is:

- Direction-locked

- ”Grid-aligned”

- Predictable and Precise

There is no drifting, no sliding, no half-turns. You either turn, or you don’t. Translating that behavior into a 3D environment (because apparently I decided two axes weren’t enough of a challenge, and future-me would deal with the consequences) meant rejecting most off-the-shelf movement solutions. Physics controllers were discarded early; they introduced uncertainty exactly where the design demanded certainty.

Pac-Ztec didn’t need realism. It needed control.

Choosing Control Over Physics

The solution was to step away from physics entirely.

Instead of relying on rigidbodies or collision responses, Pac-Ztec uses a custom waypoint-based movement system. The maze is not treated as open space, but as a network of invisible nodes. Each one represents a valid position where the player can stop, turn, or commit to a new direction.

That description sounds neat and intentional. The reality was a lot messier.

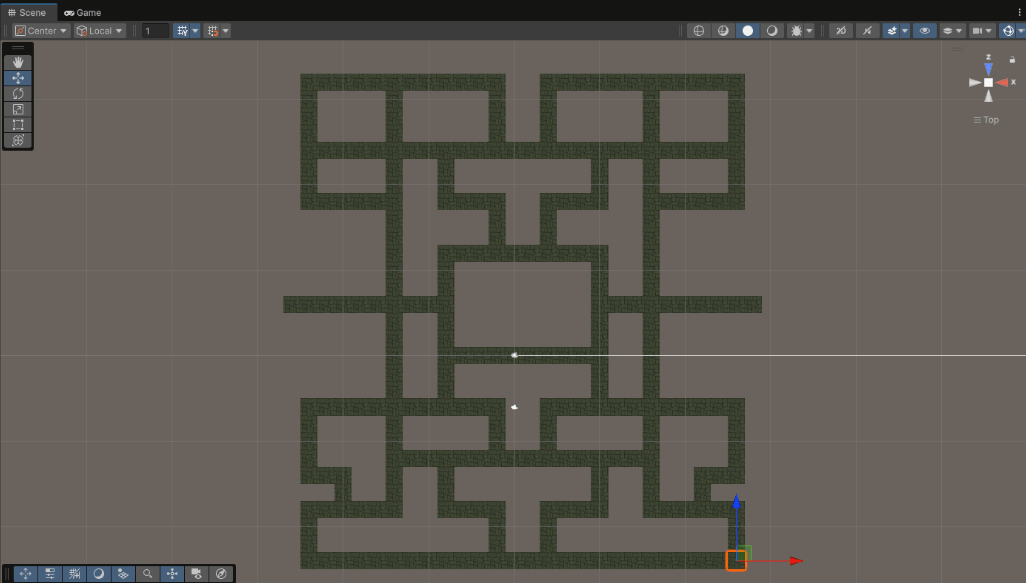

The level came first, and it was built the hard way. I recreated the classic Pac-Man maze tile by tile, manually placing each piece to match the original layout as closely as possible. I already had an Aztec-themed asset pack lying around, so I used it. Not because it was the perfect artistic fit, but because it was there and my artistic skills still don’t extend much further than Blender’s default cube. Prototypes thrive on whatever tools are within reach.

I took a single floor tile and started drawing the maze as a grid, one tile at a time… Three hundred and two tiles later (yes, I counted them) I had a complete level. Yay!

Handmade recreation of the classic pacman level… artisan work, tile by tile!.

Handmade recreation of the classic pacman level… artisan work, tile by tile!.

A few moments later, the problem revealed itself quietly: the physical size of the tiles didn’t line up cleanly with a simple world-space grid. Using raw transform positions to drive movement would have tied gameplay logic directly to level geometry, making everything fragile and error-prone. Small adjustments to scale or placement would ripple through the entire movement system. So, after taking a breath, a better idea emerged.

wait… what if… (suspense)… the level didn’t have to be the grid? (drop the mic)

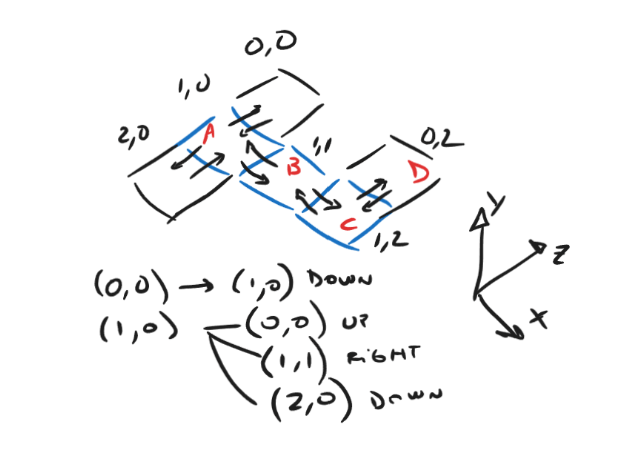

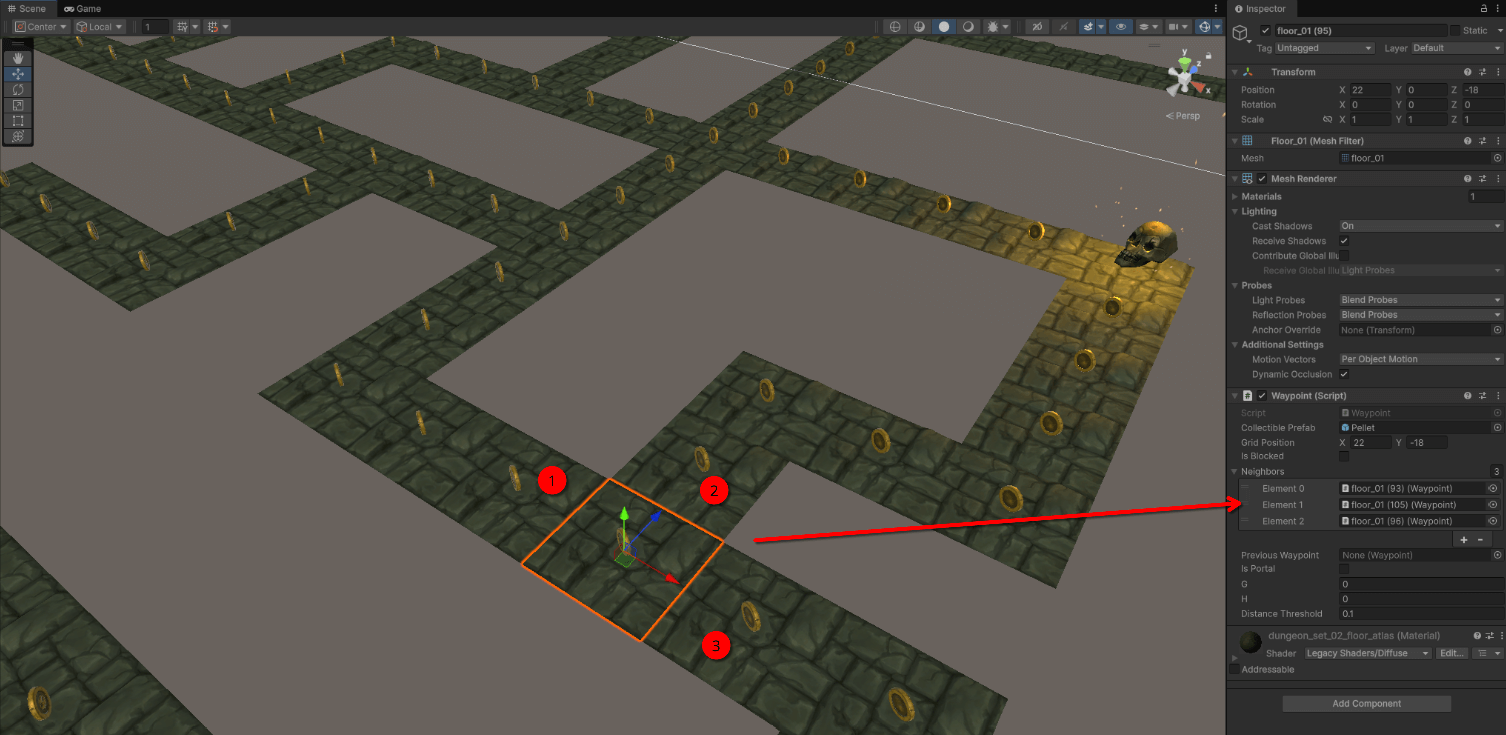

Instead of forcing the maze to behave like one, I introduced a “virtual grid” layered on top of it. Each walkable tile was given a logical (x, y) position, completely independent of its actual world coordinates. A small script (appropriately named Waypoint) became the bridge between level design and movement logic and each waypoint would define:

- Its logical position in the grid

- Which neighboring waypoints it connects to

- Which movement directions are valid from that node

Back to the board… sample of node neighbor relationships. kinda.

Back to the board… sample of node neighbor relationships. kinda.

With that abstraction in place, the player no longer moves freely through space. Movement always happens between waypoints, one segment at a time. Input is only accepted if the chosen direction leads to a valid neighbor. If it doesn’t, the input is stored and re-evaluated when movement allows it.

That single abstraction solved several problems at once:

- The player stays perfectly aligned with the grid, regardless of tile size

- Invalid turns simply cannot happen

- Movement paths become explicit and predictable

- Level design and movement rules collapse into the same system

Fortunately, all tiles were already set up as prefabs (something I learned to do after hitting that wall far too many times). That made adding waypoint logic across the entire level mostly painless.

Mostly, because the next realization hit almost immediately: now every tile needed coordinates data and manually assigning values to those 302 objects was not a path I was willing to walk… again.

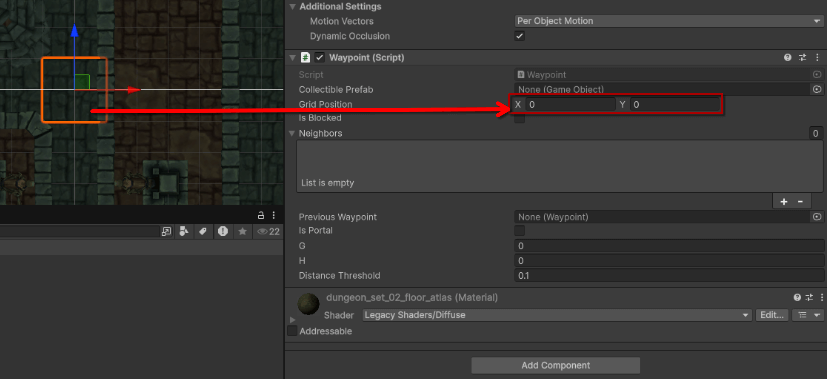

The waypoint script after a few iterations. It started with nothing more than grid coordinates.

The waypoint script after a few iterations. It started with nothing more than grid coordinates.

At this point, I created a script to act as a map manager with the solely purpose of scan the level at startup, discover every waypoint, and initialize the virtual grid automatically. Each waypoint “derives” its logical position from its transform, this is where I cheated a bit by nudging transforms until they landed on clean whole numbers. Not elegant, but effective and with that in place, the manager builds a fast lookup table so neighboring nodes can be calculated efficiently. From there, adjacency becomes a simple rule:

For each waypoint, check north, south, east, and west, using a fixed grid step If a waypoint exists at that logical position, it becomes a valid neighbor. If not, the path simply doesn’t exist.

What emerges from this is a node graph, built dynamically from the level itself. The maze defines connectivity, and connectivity defines movement. The same graph later becomes useful for other systems too—enemy navigation, scatter targets, pellet placement, and even determining valid spawn or fallback positions.

Valid destination nodes loaded dynamically for the current node.

Valid destination nodes loaded dynamically for the current node.

At this point, the grid existed, the rules existed and the maze finally knew how movement “should” work. Yay! The only thing missing was… well… movement itself.

So Far, So Good

Recreating this mechanic turned out to be anything but trivial.

Before anything could move, the game had to understand where movement was allowed, when it was valid, and why certain paths existed at all. That meant treating the maze not as geometry, but as data. It also meant accepting that a lot of early decisions would be wrong, awkward or just dirty. But each wrong turn made the right constraints clearer.

At this point, the maze wasn’t just a level anymore… kind of… fine… it was still a level okay? But it was a level with things loaded dynamically!

And don’t worry, in Part 2, I’ll finally make something move and deal with all the consequences that come with it.